HMS Trincomalee and the Indigenous Peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast

- View news filtered by: Victorian

- View news filtered by: Ships and Aircraft

- View news filtered by: HMS Trincomalee

- View news filtered by type: Blog

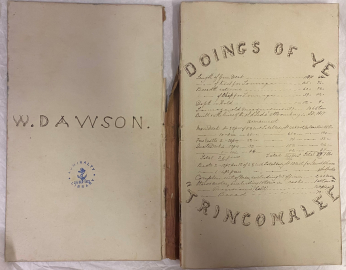

As part of her second commission (1852-57), HMS Trincomalee was despatched to the Pacific Station in 1852. She started off her journey from Plymouth Sound in August and reached Esquimalt on the coast of modern-day British Columbia in over two months. The primary purpose of having ships such as Trincomalee stationed in the north-western coast was to build what Barry M. Gough calls a ’gunboat frontier’ (Gough, 1984). The region was deemed to be in special need of gunboats from the 1850s onwards owing to the discovery of gold. Ships sought to secure British interests which, at this time, were mostly commercial. During this period, the ship interacted with Indigenous peoples of the Northwest coast. A key source of this commission to explore these interactions is a journal (NMRN Collections; WDawson MSS/87) kept by William Dawson as Sub-Lieutenant and Lieutenant on HMS Trincomalee, from 20 August 1852 to 23 March 1854.

In his journal - ‘Doings of Ye Trincomalee’ - Dawson gives us a conventional account of the ship’s journey from England, as well as personal insights into the day-to-day happenings along the coast and beyond. He mentions that canoes full of Indigenous peoples frequently came alongside the Trincomalee. In September 1853, he wrote that about 1200 different Indigenous peoples from five different tribes came alongside the ship ‘’for the purpose of trading or curiosity’’.

As these interactions took place, officers experienced new cultures and traditions. In one entry from October 1853, Dawson wrote about a local feast as follows.

‘’About the 20th large numbers of the natives of different tribes began to arrive at the Indian* Village at Victoria to honor a feast given by [?] the chief at wh. [transcriber’s note (t/n): which] he was to distribute presents consisting of 120 blankets, some muskets etc, the proceeds of a seven years collection, by doing wh. [t/n: which] he hoped to immortalize himself and hand down his name to posterity as a ‘’Great Chief’’ – wh. [t/n: which] is the sum total or rather the climax of Indian pride…The feast lasts generally 2 or 3 days at wh. [t/n: which] time they are obliged to separate for want of provisions, as the congregation of 2 or 3 thousand people together, soon brings a famine in the land – just before the end of the feast the presents are distributed, giving a musket or a certain number of blankets to each chief, in the presence of all the people, wh. [t/n: which] is done in this case from a platform – from wh. [t/n: which] remainder of the presents are distributed, the blankets being just torn up in pieces so as to go farther and make the number actually given appear greater – the real number appears to be hidden under an exaggeration, as one Indian told me there were 700 or 1700, wh. [t/n: which] shows a certain knowledge of multiplication, wh. would do credit to more skilled arithmeticians – Whilst the feast lasts dancing and gambling of wh. [t/n: which] they are excessively fond are the order of the day –’’

This journal entry suggests that this kind of feast was a local custom, organised by a chief to gain acclaim among his tribe. A close reading suggests that this feast could perhaps be the ceremonial potlatch, wherein wealth or valuables are given away alongside a programme of music, dance and oral history recitals.

*Usage of the term ‘Indian’ to refer to Indigenous Peoples of the Americas is deemed outdated and offensive. It is used in this article only as part of direct quotations from the historic journal.

Elsewhere in the journal, Dawson describes the physical appearance of the Indigenous peoples.

‘’The practise amongst the women of slitting the under lips horizontally inserting an ellipse shaped piercing of wood two or three inches long by one hand is here very common, particularly with the elderly ladies…both sexes have the ring in the nose & both also have the ears perforated with a number of large holes…They generally paint their faces red & black for the purpose I think both of adding to their decorations and preserving their flesh from sand flies…’’

The lip piercing Dawson describes here is a labret – a lip plug worn by women of the Haida people. Haida society was and is based on a matrilineal system of descent. A woman’s mouth – and thereby a labret - was considered a symbol of power as through words, a woman could mediate or agitate relations between clans. A labret, therefore, signified noble status, political influence and beauty.

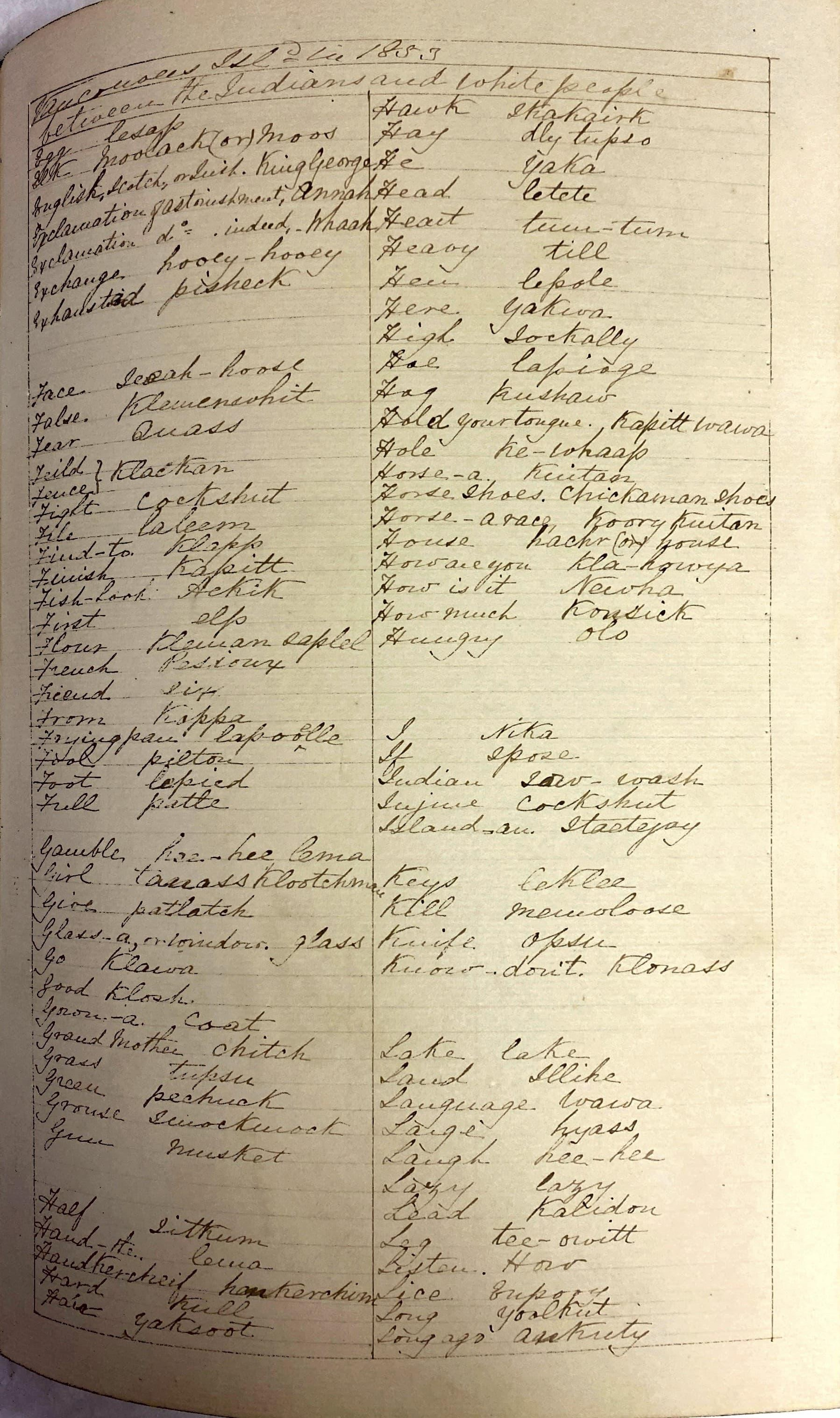

Dawson also wrote a list of Chinook Jargon (also known as Chinuk Wawa) words along with their English meanings which were used frequently. Some examples are:

Fish-hook, ik’-kik

How are you, kla-how’-ya

Otter, ne-mam’-ooks

Thanks, máh-sie

The journal mentions a very important aspect of Pacific Northwest coast culture – Haida argillite carvings.

‘’Amongst the articles purchased as curiosities were curiously carved plates & pipes etc. of a black stone somewhat like slate, Indian daggers, rattles shaped like birds & filled with stones wh. [transcriber’s note (t/n): which] are used by their doctors to frighten away diseases, and others wh. [t/n: which] rose very greatly in value in consequence of the number of buyers who were ready to [?] them up to any price, so that they might obtain them…’’

The black stone Dawson refers to is argillite or ‘kwawhlahl’. Haida people began using carvings made of argillite in the curio trade which developed by the 1820s as a result of a decline in the fur trade with foreign explorers and settlers (See examples from the British Museum’s collection). Argillite pipes were carved specifically for visitors, and gradually came to depict Euro-American motifs, including naval officers and ships. Although it started as a purely commercial art form, argillite carving has become a cultural marker of the Haida Nation and the Pacific Northwest.

The journal of William Dawson thus helps us understand Indigenous cultures and traditions of the Pacific Northwest. At the same time, it gives us interesting insights into the socio-cultural dynamics of between the Royal Navy and Indigenous people of British Columbia, allowing us to build a more granular and holistic understanding of the period.

Sources and further reading:

Barry M. Gough, 1984. Gunboat Frontier: British Maritime Authority and Northwest Coast Indians, 1846-1890. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Marius Barbeau, 1953. Haida Myths: Illustrated in Argillite Carvings, National Museum of Canada, Bulletin no. 127, Anthropological series, No. 32, Ottawa: Department of Resources and Development, National Parks Branch, National Museum of Canada.

PRM Body Art Collection, Pacific NW coast mask and labrets. Oxford: Pitt Rivers Museum. https://web.prm.ox.ac.uk/bodyarts/index.php/permanent-body-arts/reshaping-and-piercing/157-pacific-nw-coast-mask-and-labrets.html (Last accessed on 7 June 2024).

Sir James Douglas to Pelham-Clinton, 5th Duke of Newcastle Henry Pelham Fiennes 28 July 1853, CO 305:4, no. 9499, 73. The Colonial Despatches of Vancouver Island and British Columbia 1846-1871, Edition 2.0, ed. James Hendrickson and the Colonial Despatches project. Victoria, B.C.: University of Victoria. https://bcgenesis.uvic.ca/V53208.html (Last accessed on 7 June 2024).

Widdowson MSS/87. Doings of Ye Trincomalee. Manuscript journal kept by William Dawson. National Museum of the Royal Navy