International Women's Day 2022

- View news filtered by: Navy Origins

- View news filtered by: Naval Lives

- View news filtered by: Women in the Navy

- View news filtered by type: Blog

For centuries women were written out of history in favour of male explorers, valiant fighters and educated thinkers. There remain many gaps between the rare photographs and written word that capture women’s thoughts, feelings and experiences that we may never fill.

Museum collections are vital in capturing even the smallest snapshot of women’s lives and have a responsibility to elevate these voices and experiences.

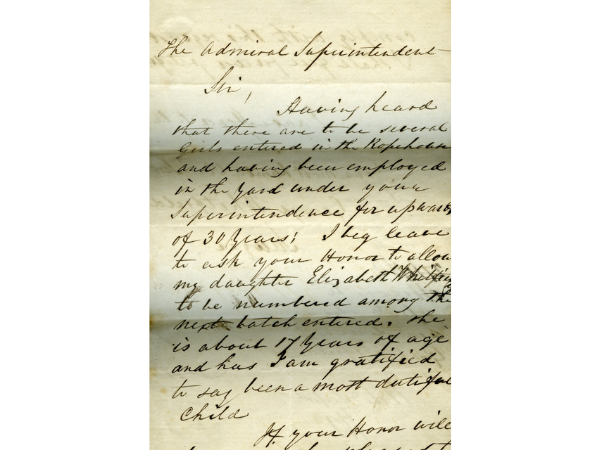

Pure luck meant that a collection of letters written by uneducated, working-class women begging for dockyard work in Devonport in the 1800s were kept on file long enough to be donated to our small naval museum.

Such societal status usually meant these women were ignored or forgotten, yet even this small collection is rich in what it can tell us. These women paid scribes to write on their behalf, they were desperate, they had perhaps been bereaved, or had become the head of their households.

Ropery Letter, Devonport Collection

To find such stories, you must be prepared to dig deep and find little. Historian, Dr. Erin Spinney, trawled the National Archives for hours to find limited evidence of black women working as nurses in Royal Naval hospitals across the Caribbean.

She found records of enslaved women of naval pay lists, but learnt little more about them. But in this instance, it is the lack of evidence that speaks volumes about how much society valued black women, particularly enslaved black women. We’ve all heard of Florence Nightingale; ‘The Lady with the Lamp’, but how many nurses of black or different ethnicities can you name?

Today there has been – and continues to be – a shift towards recording and researching lost, forgotten, and undervalued histories. So much so that we understand the importance of recording these stories before we consider them history.

More women in modern times have fought their way to the front and made successful careers for themselves. And, more women today are educated and able to document, record and share their histories themselves.

‘Jimmie’ Joy Spottiswoode-Clarke

By the Second World War, women were established in the workplace, filling the roles men had left for the Front Line. In 1947, ‘Jimmie’ Spottiswoode-Clarke joined the Women’s Royal Naval Service as an Aircraft Mechanic. She was promoted to Leading Wren in 1949.

Just a year later she made Petty Officer Wren, and Chief Wren by 1953. She was awarded her Long Service and Good Conduct Medal in 1969.

Lieutenant Commander Becky Frater

Following a decade in the Army Air Corps, Lt Becky Frater gained her Royal Navy Wings in 2007, joining the Maritime Lynx Training Squadron.

Her military careers saw tours of Belize, Afghanistan, and Iraq to name but a few, and she became the first woman to achieve the following: first to pilot the Helicopter Maritime attack Lynx, first qualified helicopter instructor, first to fly an FF Display Helicopter and FF Display Team (first in the world to lead a military helicopter display team), and first female to command a naval air squadron.

Their stories reside at NMRN’s Fleet Air Arm Museum, offering a glimpse into the life of naval women.

Breaking the glass ceiling

It is a privilege to learn of any of these women, but we need only turn our attention to the modern day to see why such stories remain so rare.

It was not until January of this year that the first woman – Jude Terry – rose to the rank of Rear Admiral, making her the most senior woman in the naval force, past or present.

Despite women serving in the Navy since the First World War, there are only four female Commodores, and 20 female Captains.

But Terry remains positive about the future for women making history, stating that the numbers, breadth of talent and experience means she will not be the last in her rank, and many will go higher.