The British Special Service Squadron - March 1924

- View news filtered by: Interwar

- View news filtered by: Navy Organisation

- View news filtered by: Specialisms

- View news filtered by: Units & Squadrons

- View news filtered by: British Special Service Squadron

- View news filtered by type: Blog

In this ongoing blog series, the National Museum of the Royal Navy is following the route of the British Special Service Squadron during the centenary of its voyage. In this entry we discuss their travels from East Asia to Australia.

The squadron had 2,300 miles to travel between the Federated Malay States (now Malaysia), and Australia and had to cope with some challenging weather conditions. A heavy swell prevented a planned stop at Christmas Island (or Kiritimati) and 21 February 1924 was recorded as extremely rough:

"In the afternoon the wind was howling through the rigging and huge seas broke over the quarter deck... The light cruisers looked very uncomfortable. At times their forecastles would descend below the surface to be lifted an instant later high above it, bring with it several tons of green seas." RNM 1999/31. Wilfred Woolman.

The crew also found the tropical heat difficult, with accidents becoming more frequent. The men suffered with heat-related diseases which affected the effectiveness of the crews. The health of personnel was recorded in regular reports, known as Statistical Reports of the Health of the Navy. It was also important to keep up morale and a fresh supply of films had been picked up in Singapore, which were broadcast during leisure periods. Though during calmer days routine tests and trials continued, including smoke screens, and firing trials.

Western Australia 27 February – 6 March 1924

"On the ninety-third day of our voyage since leaving Chatham and Plymouth in the fog of a cold November morning, we cast anchor in Fremantle harbour" O’Connor p.122

The squadron was warmly welcomed on its arrival to Australia on 27 February 1924; although it was also to be a delicate diplomatic event. The official programme included visits to the Governor, the Premier and the Mayor of Perth. There was also a march through Fremantle and Perth, the schoolchildren in the metropolitan area being given a holiday so they could be shown over the ships.

There were international discussions on the development of Singapore naval base in progress, including financial contributions from other countries of the British Empire including Australia. Australia was invested in the development as they had concerns about Japanese expansionism in the Pacific after the earlier Russo-Japanese War (1904–05). The press contained articles, such as this piece in The Herald (Melbourne), speculating if Japan was ‘following a deliberate, long-sighted scheme to impose her will and her people upon foreign soil…’ or all the apprehension felt since Japan's success against Russia was without substantial basis’. (Cullet, 12 January 1924)

The official position of the Australian government was supportive of the Royal Navy. Sir James Mitchell, the Premier of Western Australia at an official lunch on 29 January 1924 gave a speech:

"To Australia as to Britain, the Navy means everything... our great settlements are around the coast. Without the dominant British Navy, we would be utterly destroyed. Without the Navy the Empire would not exist, and without the Empire the world lose its greatest guarantee of peace..." Sir James Mitchell

This view was not held universally, with other press pieces calling out that Britain was ‘only using the Empire cry for her own ends, and Australia in particular as a dumping dominion for surplus population and shoddy goods’. (The Labor Call, 27 March 1924). The dominions, which had fought alongside Britain during the First World War were pushing for more than self-governance but for equal status. This was achieved only two years later, in 1926 Britain and the dominions agreed that they would all be equal in status (the Balfour Report).

After a busy three days of ship visits and functions, the Squadron left Freemantle on the morning of Saturday 1 March, with many people on the quayside to see their departure.

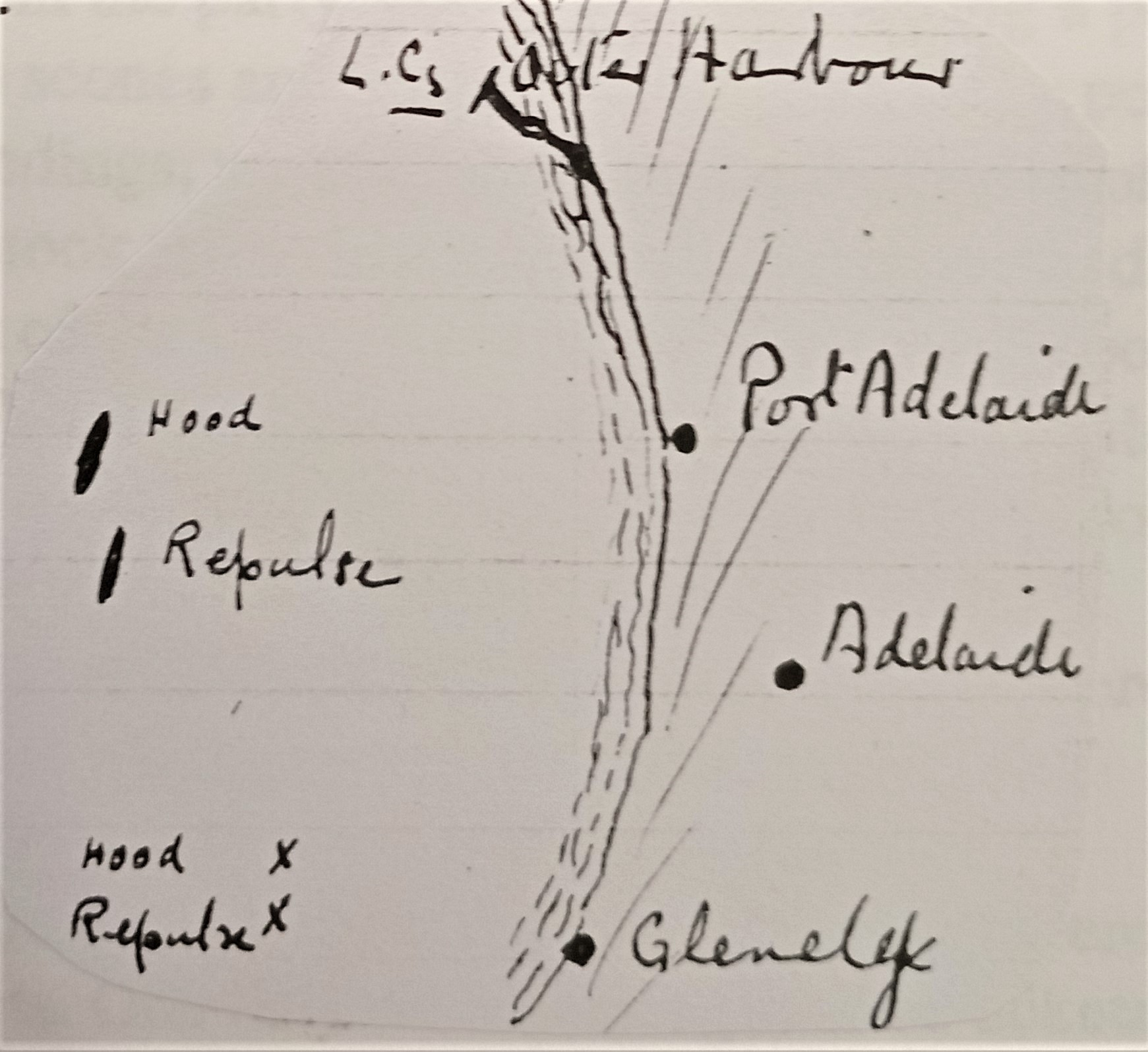

The squadron reached Albany, Australia late on 2 March 1924 with HMS Hood and HMS Repulse anchoring in King George's Sound some four miles from the town and the cruisers in the inner harbour. Albany was a popular seaside resort for the area and the crews spent three days enjoying a more relaxing schedule after Fremantle and before moving on to Adelaide.

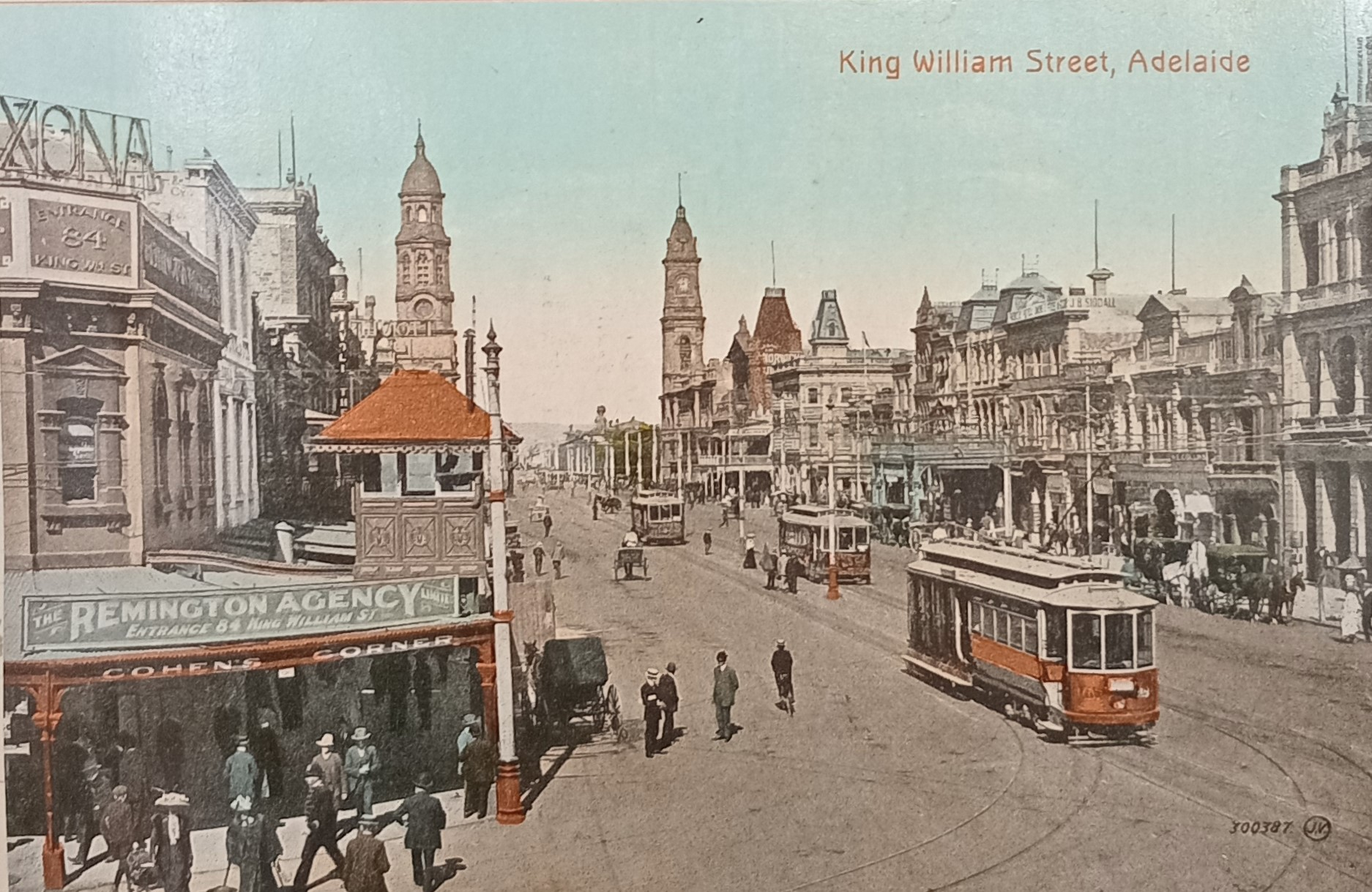

South Australia 10 – 15 March 1924

On arrival at Adelaide, the capital of South Australia, the two battle cruisers anchored nearly six miles from Port Adelaide while the light cruisers berthed on the jetty at Outer Harbour. Admiral Field decided the water was too shallow to bring the big ships alongside, but this left them barely visible from shore to the disappointment of local visitors. After the official reception it was decided to move the big ships to Glenelg (about six miles by rail), but as the Schoolmaster of Repulse recalled in his diary for Monday 10 March 1924:

"...the ship was open to visitors from 2 to 6pm but not a single soul appeared on board, deterred undoubtedly by the two hour journey each way from Adelaide. The light cruisers, however had a full quota."

A ceremonial march took place on Tuesday 11 March involving 1,600 officers and men, with lunch provided afterwards. The men of the Squadron were being entertained on a grand scale, but the battle cruisers left Glenelg on 15 March, with only a few enthusiasts to see their departure.

Melbourne 17 – 25 March 1924

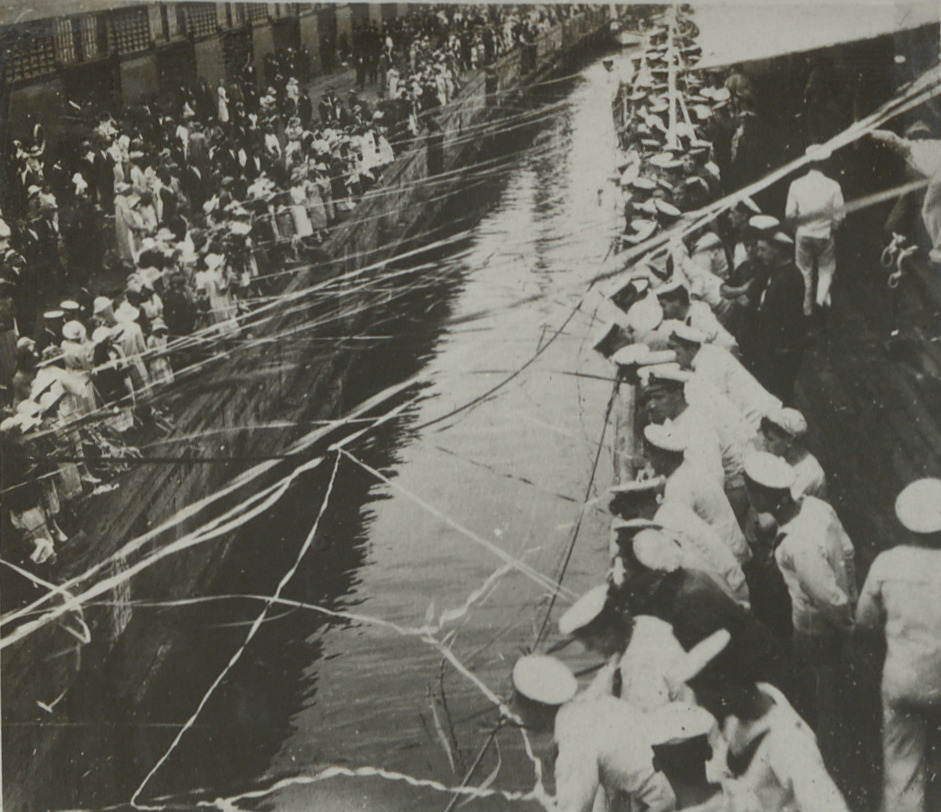

Melbourne surpassed all previous welcomes the British Squadron had received. On 17 March HMS Hood and HMS Repulse passed through the sea passage at Port Phillip Heads (50 miles from Melbourne):

"Just inside the entrance we were met by a large number of yachts filled with cheering humanity... the whole distance we steamed through lines of boats of every description filled with men, women and children enthusiastically waving... and yelling themselves hoarse.’" RNM 1999/31. Wilfred Woolman

On the following day, 18 March, the British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald announced to Parliament that his government was suspending construction of the Singapore base in the interest of austerity and international peace. The government concluded the base was expensive, unnecessary, and contrary to the disarmament spirit of the Washington Treaty. The news was discussed in the Australian national and local press ‘...the unpleasant fact is that Australia and New Zealand have now to face is that they will have to rely more on themselves than they have ever done in the past’. Sydney Morning Herald, March 19, 1924.

At an official dinner at which there was an outlining the Commonwealth naval policy, the Prime Minister (Mr. Bruce) criticised the British Government's decision to abandon the Singapore base project. Vice-Admiral Sir Frederick Field, in replying to the toast of the visitors, advised Australia about the replacement of obsolescent cruisers. (Friday 21 Mar 1924. The Argus).

Despite the uncertainty, the people in Melbourne and the surrounding area welcomed the sailors. On opening HMS Hood up to visitors, they, ‘lined every foot of deck space, climbed every ladder, adorned every excrescence upon which a man could stand’. (Benstead, 1925). Charles Benstead, an officer of HMS Hood also estimated that on Hood's first afternoon in Melbourne alone, over 30,000 people visited the ship. An extensive range of entertainments was provided for the crews, including dinner at State Government House, the Lord Mayor’s Ball, excursions into the country, free admission to local attractions and the Governor’s Ball at the Wattle Path Palais (a huge ball room with about 2,000 guests).

"Just inside the entrance we were met by a large number of yachts filled with cheering humanity... the whole distance we steamed through lines of boats of every description filled with men, women and children enthusiastically waving... and yelling themselves hoarse." RNM 1999/31. Wilfred Woolman

On the following day, 18 March, the British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald announced to Parliament that his government was suspending construction of the Singapore base in the interest of austerity and international peace. The government concluded the base was expensive, unnecessary, and contrary to the disarmament spirit of the Washington Treaty. The news was discussed in the Australian national and local press ‘...the unpleasant fact is that Australia and New Zealand have now to face is that they will have to rely more on themselves than they have ever done in the past’. Sydney Morning Herald, March 19, 1924.

At an official dinner at which there was an outlining the Commonwealth naval policy, the Prime Minister (Mr. Bruce) criticised the British Government's decision to abandon the Singapore base project. Vice-Admiral Sir Frederick Field, in replying to the toast of the visitors, advised Australia about the replacement of obsolescent cruisers. (Friday 21 Mar 1924. The Argus).

Despite the uncertainty, the people in Melbourne and the surrounding area welcomed the sailors. On opening HMS Hood up to visitors, they, ‘lined every foot of deck space, climbed every ladder, adorned every excrescence upon which a man could stand’. (Benstead, 1925). Charles Benstead, an officer of HMS Hood also estimated that on Hood's first afternoon in Melbourne alone, over 30,000 people visited the ship. An extensive range of entertainments was provided for the crews, including dinner at State Government House, the Lord Mayor’s Ball, excursions into the country, free admission to local attractions and the Governor’s Ball at the Wattle Path Palais (a huge ball room with about 2,000 guests).

"In addition almost everyone made friends and were entertained privately, I received an invitation from a young Jewish lady… on Saturday I was invited to the synagogue and afterwards dinner at the minister’s house (Rev Danglow)" RNM 1999/31. Wilfred Woolman

The ships departed Melbourne on 25 March. On leaving Admiral Field, in charge of the Squadron notified the Admiralty that ‘it cannot be fully realized in England with what consternation this decision has been received in Australia and I should be failing in my duty if I did not record the impression conveyed to me that this decision has been generally received in Australia with genuine feelings of alarm’. (TNA, ADM 116/2254).

Their next destination was Hobart, Tasmania. Come back next month to hear about the next leg of the squadron’s journey.

In the meantime, if you want to learn more about the British Special Service Squadron you can search our Collection.

Sources and further reading

Benstead, Charles Richard. Round the World with the Battle Cruisers. Hurst and Blackett, Limited, 1925

Harrington Ralph. The Mighty Hood': Navy, Empire, War at Sea and the British National Imagination, 1920-60 Source: Journal of Contemporary History, April, 2003, Vol. 38, No. 2 (Apr., 2003), pp. 171-185

Mitcham, John C. The 1924 Empire Cruise and the Imagining of an Imperial Community. Britain and the World, March 2019, vol. 12, No. 1 : pp. 67-88

Cullet, H.S. Can Japan live at home or is overflow inevitable? A Survey from the Australian Angle

The Herald (Melbourne, Victoria : 1861 - 1954) Sat 12 Jan 1924 Page 6

Scott O’Conner, V.C. Empire cruise. London : 1925. - First edition. - 301p

RNM 1988/259 Private diary kept by Chief Petty Officer William Arthur Russell of the Empire Cruise of the British Special Service. HMS Repulse

RMM 2015/50 diary, 'Empire Cruise 1923-1924: Hood-Repulse', kept by Bugler R Newman, dated 27/11/1923-28/9/1924.