British Special Service Squadron - September 1924

- View news filtered by: Interwar

- View news filtered by: Navy Organisation

- View news filtered by: Specialisms

- View news filtered by: Units & Squadrons

- View news filtered by: British Special Service Squadron

- View news filtered by type: Blog

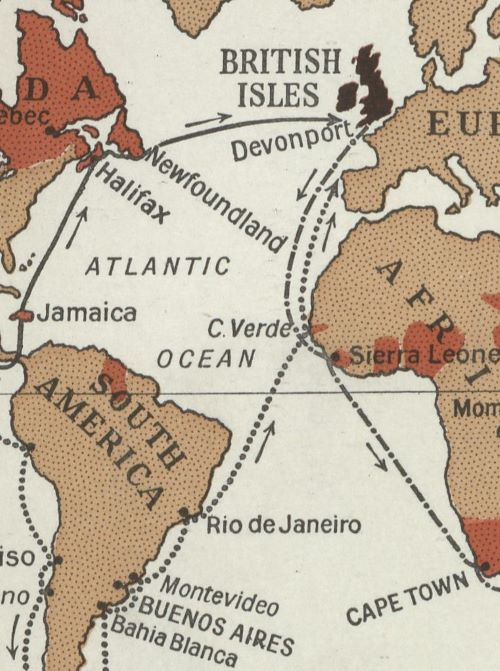

In this final instalment of the blog series, the National Museum of the Royal Navy follows the final movements of the British Special Service Squadron during the centenary of its voyage. In this entry, the core element of the Special Service Squadron comprising HMS Hood, HMS Repulse and HMAS Adelaide are visiting Newfoundland. The Light Cruiser Squadron is separately sailing around South America, reaching Brazil before heading home across the Atlantic Ocean.

Special Service Squadron (HMS Hood, HMS Repulse and HMAS Adelaide) Departure from Quebec – Tuesday 2 September

'The trip to Topsail Bay [Newfoundland] occupied 4 days, in which we were treated to many different samples of weather - mist and ran, glorious sunshine and glassy water, wind and heavy seas, thunder and lightning and more fog followed us until 1.30 on Saturday (Sept 6) we dropped anchor in the quiet of Topsail Bay’. RNM 1999/31.

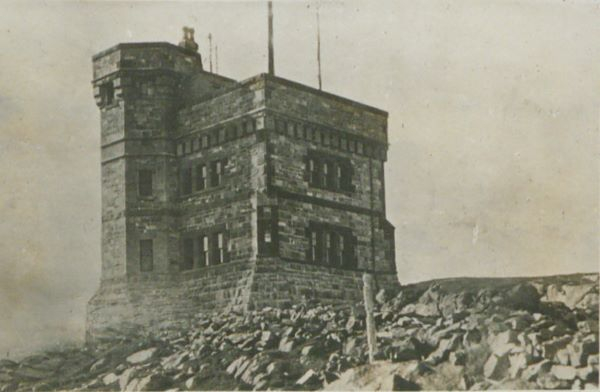

Newfoundland, a former British colony, had been granted dominion status during the 1907 Imperial Conference. The conference decided to no longer refer to self-governing British colonies, such as Newfoundland, as colonies and conferred upon them dominion status instead. The harbour at St John's, the capital, was too small to accommodate the battle cruisers, so they anchored off Topsail Bay. This was 14 miles from St John’s, but the Government of Newfoundland arranged free trains which took 40 minutes, and officers were put up by residents following late night events.

The visit was marred and some of the festivities cancelled after two officers from HMS Constance, Lieutenant Commander Denys O'Callaghan and Lieutenant Edmund Burrows were killed in a motor accident on 16 September.

'One of these, Lieutenant Burrows, was to have taken passage home in the Repulse... they were returning to St John's from Topsail, where they had been entertaining. The party ran into a part waiting to board a bus, killing two on the spot. The car then dashed across the road, crashed into a telegraph post and overturned, killing the two officers and two other occupants on the spot.' RNM 1999/31.

HMS Constance had already been in Newfoundland as part of the North America and West Indies Station with 8th Light Cruiser Squadron. The station was a regional command, which after the First World War patrolled the North Atlantic, West Indies and North Pacific-from the Galapagos Islands to the Bering Straits.

Two days later the band of HMS Hood, with muffled drums, led the funeral procession for the two officers. The band was followed by a detachment of sailors from the four Special Service warships, ahead of the gun carriages carrying the coffins and escorted by officers and 50 petty officers, carrying wreaths. Among the mourners were the premier of Newfound, Premier Monroe and members of the executive government.

The time in Newfoundland therefore ended up being quiet; between the distance to St Johns, crew members trying to save their remaining leave for time ashore when they got home, and the tragic accident meant that many stayed on board and arranged entertainment on the ships instead. On the last night though, 20 September, the Warrant Officers of HMS Repulse were invited to dinner by the Warrant Officers of HMS Hood.

Departed Canada, bound for England- 21 September 1924

‘At 5.15pm got underway. Quite a number of people came out in small boats to see us go. At long last, we have completed our cruise and are out on the home trail.’ RNM 1999/31.

Light Cruisers - Rio de Janeiro, Brazil - 3 September

The light cruisers arrive off Rio de Janeiro, Brazil where they were welcomed by two Brazilian destroyers who escorted them into the harbour.

‘The city has the indefinable scent of the tropics about it; the main street and those leading off it are very fine... the rest of the streets are very dirty and dilapidated.' RNM 1987/497/26

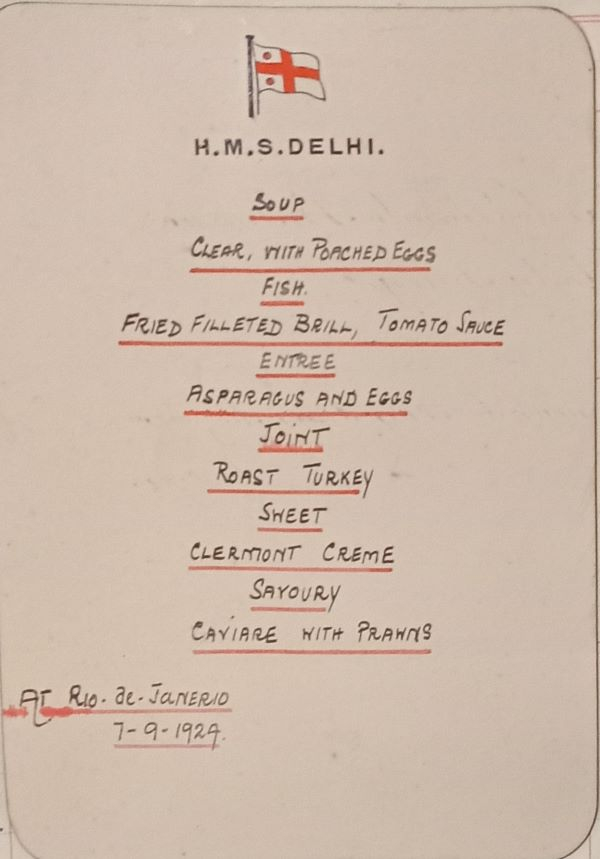

Brazilian Independence Day was celebrated on 7 September with 21-gun salutes fired at sunrise, noon, and sunset. 500 officers and men took part in the official march past, with 2,000 Brazilian seamen and marines under the charge of Rear Admiral Thompson, Brazilian Navy (Marinha do Brasil). The Brazilians had fought for independence from Portugal between 1822-1824, their independence formally recognized in 1825 by Portugal and the United Kingdom. The day concluded with Rear Admiral Brand hosting a dinner party on HMS Delhi.

The cruisers left on 10 September 1924, HMS Dragon departing first at 0900, HMS Danae 0930 and the rest of the cruisers at 1015. The departure was recorded by Instructor Lieutenant William Bishop who observed

‘very few people assembled to see us off and mostly Brazilians … certainly don’t go much on the British Community here, they are about the most mixed crowd I’ve seen’ RNM 1987/497/26.

They may have been glad to depart. The political situation in Brazil was unsettled during their visit. Brazilian Presidents had been traditionally chosen from only two of the larger states of the country and the smaller regions had begun to protest this in 1922. There had been active fighting in São Paulo (the regional capital of São Paulo state) during July 1924. Some of the Brazilian Navy mutinied only eight weeks after British light cruisers had sailed. Despite the internal tension, the visit of the light cruisers went well, and they were now bound for home, with only a brief stop at the Cape Verde Islands.

At Sea - 28 September 1924

Having travelled as separate squadrons since their departure from San Francisco in July, the battlecruisers temporarily rendezvoused with the First Light Cruiser Squadron off the Lizard, the most southerly point of mainland Britain.

‘On Sunday afternoon, in hazy weather... our light cruisers which had made the return trip round South America came into view... About 4.30 they split into two groups, the Danae and Dragon turned round and steamed between two lines of ships - Hood, Repulse and Adelaide in one line, Delhi and Dauntless in the other. The ships' companies cheered one another as they passed and then the Dragon and Danae set their course for Chatham. The Repulse and Adelaide cheered Hood, Delhi, and Dauntless and increased speed to make for Portsmouth, the remaining ships proceeding to Devonport.' RNM 1999/31.

Homecoming - 29 September 1924

Most of the crews, their families and friends were delighted and relieved to be home, but it was not a joyous occasion for all. Eight men had died during the cruise, the last being Harold Martin in HMS Dragon passing from illness on 14 September, less than three weeks from home.

At Devonport ‘the night of our arrival at Cawsand Bay, the wardroom door [of HMS Hood] suddenly flew open as if a hurricane had pushed it in, and the President of the Mess appeared... and called out in a loud voice 'THE DELHIs'...what a meeting of Opposite Numbers and rejoicing and small drinks, and tales to tell! It was like the first day of the holidays O’Connor p.266

At Portsmouth Repulse and Adelaide arrived off Spithead a little before noon...We entered Portsmouth Harbour and berthed alongside the railway jetty. Here a number of relatives had assembled. The arrival was marked by a pathetic scene. On the jetty could be seen a little woman supported by two policemen. As the ship drew slowly alongside, this poor woman was seen extending her hands towards the ship for one she could not meet. We guessed this was the widow of Electrical Artificer Hickman, who lost his life while canoeing at Halifax [in August] .... Our hearts went out to her in her sore affliction, but would it not have been better for her to have kept away. RNM 1999/31.

At Chatham ‘30 September … Nice fine day. Slipped [left mooring at Sheerness] at 1200 and came up to Chats [Chatham] passing two hulks...one of which I believe was the Inflexible. Also passed Comus with no-one on board and two awful looking aeroplane carriers. A small crowd cheered us at Gillingham Pier and all the wives came up with us from Sheerness.’ RNM 1987/497/26.

The outcomes of the cruise.

There were differing views on how the cruise was received after it ended. The Royal Navy thought it had gone quite well; Admiral Jellicoe addressing a Royal United Services Institute meeting in 1926 stated

It is impossible to exaggerate the value of that visit... such a visit should be paid every three or four year in order that our kinsfolk overseas may realise the development of our Navy, and the fact it is still in being, and growing more efficient with every day that passes.... the fact of HMAS Adelaide joining the Special Service Squadron, being the first case in which there was an interchange of ships between the Dominion Navy and the Imperial Navy. Again, I would like to emphasise the exceeding value of that interchange, ship after ship is being exchanged between the Imperial Service and the Royal Australian Navy... I hope that in addition to the exchange of ships we shall see also an exchange of personnel. The more the two navies mix, the better it will be for both.’ RUSI, 1926 p.321.

The Royal Navy may have perceived it as a success, but this view was not widely shared across the Empire. A film had been made to accompany the cruise entitled ‘Britain’s Birthright’. It was a media opportunity to reflect on the unified strength of the independent dominions together, but instead bluntly reinforced the concept of ‘Empire’ in just a two-word title. Possibly unsurprisingly, the film was ‘refused by all the Dominions’ and only shown by private enterprise (The Times, 24 May 1926, xiv). Daniel Knowles in his recent book on the Empire Cruise considers the increasing impact of America on the popular film market, but even with the expanse of the British Empire (24 per cent of the World’s land mass in 1920), the film was a flop.

A commemorative book was written by a travel writer of the time, Vincent Scott O'Connor. It views the cruise through the staunch glory of the Empire lens, not questioning the dichotomy in race but gives an insightful view into Inter-war international diplomacy, the ethics of naval visits to other cultures before the development of the ethnographic tourist, and a clear view of how Britons felt about the Empire at the time. In Penang O’Connor noted '

the Empire offers a place of honour and consideration to those of its peoples who are not of British race, that many are well able to fill it, and that they prosper here more greatly under our rule than under their own' p.101, while the Québécoise were considered that they could be won over ‘if they are treated with generosity and a just regard for their rights. p.262. But of the Aborigines he spoke 'The poor Black man has already gone, and his memory survives now... only in the strange place-names he has left behind him...It is a world beyond knowledge and over large portions of it bare and destitute’ p.131

As explored in this blog, the British Special Service Squadron was a considerable undertaking. The ships and their crews had the opportunity of working in different operational environments, gained practical experience of international ports and meeting people from other nations and navies. In fact, 1,936,717 people visited the ships during their journey across the world, in addition to those met at functions and social calls. It prompted necessary, although sometimes difficult discussions about nation states and their standing in the international community, specifically their status within the Empire. For his efforts Rear-Admiral Frederick Field was promoted to Vice-Admiral in 1924 on their return to Devonport.

Ultimately, though as author John Mitcham summarises:

A closer examination of the cruise, though, reveals the Janus-faced nature of the British world system in the 1920s. The rhetoric of imperial unity espoused by overseas Britons – of racial solidarity, Britishness, and a common maritime heritage – reflected fading, Victorian ideas of Greater Britain.…. However, this discourse coexisted with efforts in the Dominions to steer their own course and to resist closer formal ties with London… Ultimately, the navy's historic voyage was an exercise in imperial propaganda based on a vision of the British Empire on which the sun was rapidly setting. Mitcham, 2019

Dedicated to those who did not return:

John Telfer, Able Seaman, HMS Dunedin 18 January 1924

George Wood, Stoker Petty Officer, HMS Repulse 29 January 1924

Walter Benger, Able Seaman, HMS Hood 5 February 1924

Henry Layfield, Marine, HMS Delhi 17 February 1924

Alfred Punshon, Commissioned Signal Boatswain, HMS Hood 25 March 1924

William Harrhy, Able Seaman, HMS Dauntless 18 April 1924

Leonard Hickman, Chief Electrical Artificer, HMS Repulse 10 August 1924

Harold Martin, Able Seaman, HMS Dragon 14 September 1924

This blog series has highlighted much of the work currently ongoing at the National Museum of the Royal Navy on how we interpret the legacy of the British Empire, the Royal Navy’s part in this story and its impact on global history. If you would like to learn more about this important work and upcoming projects which continue to address this history and the work of our Addressing Empire group, please get in touch at Collections.Research@nmrn.org.uk

Sources

Daily Colonist, Canada. Rehabilitating Esquimalt 16 July 1919 p.4

The Evening Advocate, Newfoundland 18 September 1924, reporting the funeral proceedings

Harrington, Ralph, 'The Mighty Hood': Navy, Empire, War at Sea and the British National Imagination, 1920-60’, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 38, no. 2, April 2003, 171-185.

Irving, John. Naval Life and Customs: Tradition, Lore, and Language of the Royal Navy. Sherratt & Hughes, Altringham [1944].

Knowles, Daniel. Empire Cruise: The Special Service Squadron 1923-24. Fonthill Media 2024

Mitcham, John C. The 1924 Empire Cruise and the Imagining of an Imperial Community. Britain and the World, March 2019, vo. 12, No. 1: pp. 67-88

RNM 2015/175/4 Letters of Captain Charles Round-Turner to his wife. 1923-1924

RNM 1987/497/26 Diary kept by Instructor Lieutenant W.A. Bishop, HMS Danae

RNM 1999/31. Woolman, Wilfred. Typescript transcription of a diary kept by Wilfred as Schoolmaster in HMS Repulse during the world cruise of the Special Service Squadron, 27th November 1923 - 29th September 1924. Transcript by his son Aubrey Woolman

Scott O'Connor, Vincent Clarence. The Empire Cruise. Riddle, Smith & Duffus, 1925