Pride Month 2023 - What are 'Crossing the Line' ceremonies?

- View news filtered by: 21st Century

- View news filtered by: Naval Lives

- View news filtered by: Communities

- View news filtered by: Trailblazers

- View news filtered by type: Blog

To commemorate Pride Month the National Museum of the Royal Navy has produced a short series of blogs detailing the long and complicated history of LGBTQ+ service people and the Royal Navy. It is important to be open to discussion regarding this difficult history and recognise the struggles, discrimination, and in some instances danger to life, faced until relatively recently. This is also the time to celebrate on the progress made in LGBTQ+ rights and reflect on the steps it has taken here.

This June the National Museum of the Royal Navy Portsmouth were present for the first time at Portsmouth Pride*, where we shared space with Compass The first blog in the series explores what life was like for LGBTQ+ service people prior to acceptance within the Armed Forces and how they may have found the freedom to express themselves before Pride.

*The content below was part of the National Museum of the Royal Navy’s display at Portsmouth Pride.

Crossing the Line Ceremonies: cross-dressing and genderfluidity in the Royal Navy

It was not until January 2000 that gay, lesbian, and bisexual people were legally allowed to serve in the Armed Forces, after a significant legal battle, known as Smith & Grady v UK, at the European Court of Human Rights found that the investigation into and subsequent discharge of personnel from the Forces on the basis of their sexuality was a breach of their right to a private life under Article 8 of the European Court of Human Rights. The same rights were not granted to trans+ people until 2014.

Before this time, any form of queer self-expression was at best, difficult, and at worst, extremely dangerous. Thankfully, today, LGBTQ+ people are celebrated in the Forces, and where better to do so than at Pride? But how, if at all, did people within the Royal Navy present their sexuality or gender identity before the lifting of the ban, and before Pride?

Crossing the Line

Crossing the Line ceremonies have taken place whenever a naval ship has crossed the equator since the 18th Century. All crew members who have not crossed the ‘line’ before, regardless of age or rank, participate in the initiation ritual. The ceremony begins with the procession of King Neptune, who opens his Court and addresses the captain of the ship and his men. The first inductee is called for and seated above a pool of angry “bears”.

The inductee is given a medical by a “doctor”, a pantomime performance with oversized instruments. The outcome is usually the giving of ‘medicine’ in the form of a large pill or spoonful of foul ingredients. Next, the inductee receives a shave from the ship’s “barber”, dressed to resemble a bloodstained butcher. He uses a large wooden razor blade and foam made consisting of flour and water. The dunking commences by men dressed as bears, who continue to dunk the inductee until satisfied; the dunking of an Officer is often more prolonged. The sailor then becomes part of the Order of The Deep.

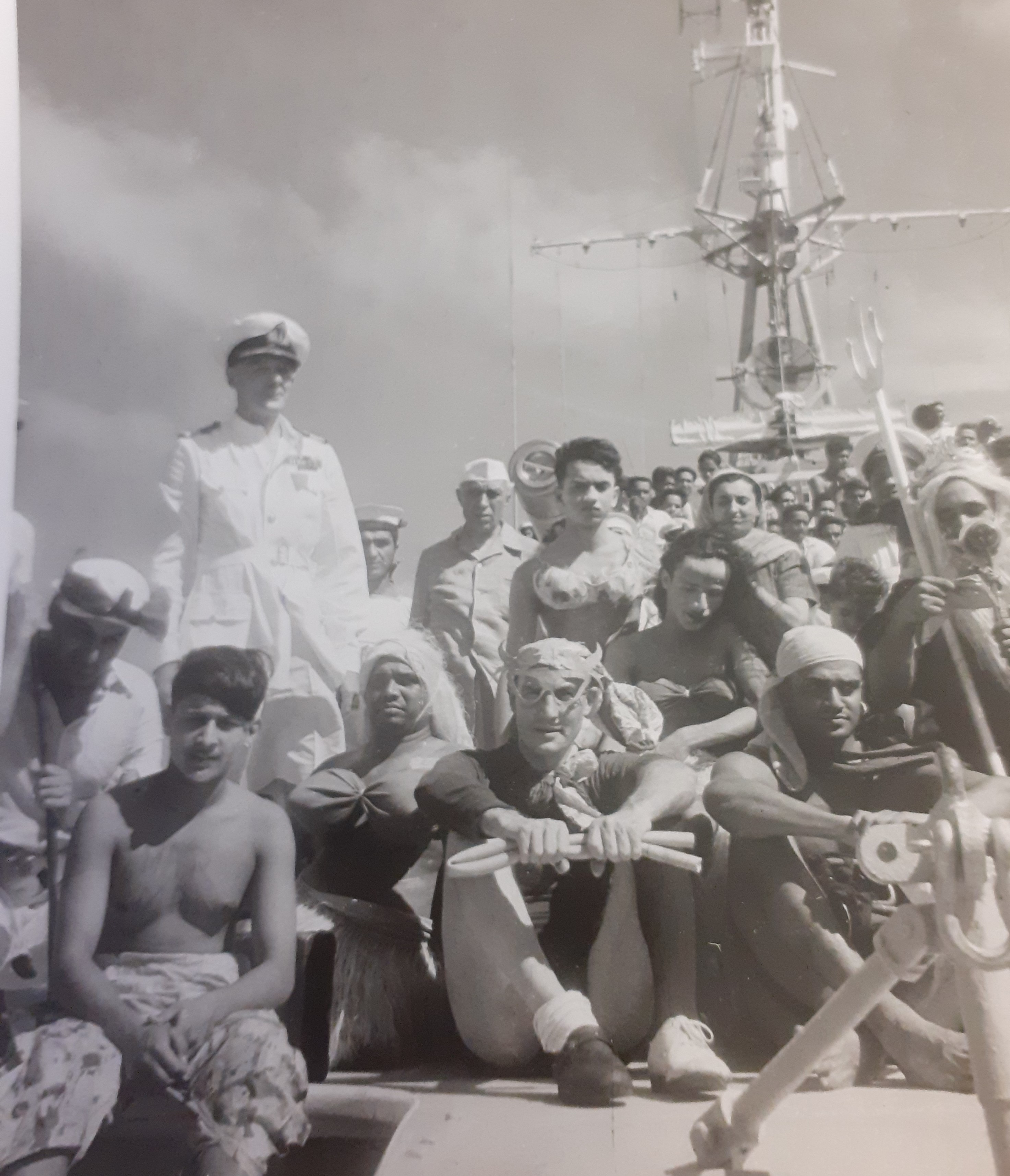

Crossing the Line ceremonies have always featured fancy dress, including men in female attire, or drag, and is a practice that remains today, raising some interesting questions.

Crossing the Line Ceremonies - images from the NMRN Collection

Can we take this as evidence of cross-dressing and/or gender fluidity within the Royal Navy?

This is a difficult question. We cannot ask the people who took part historic ceremonies, such as those in the photographs featured, whether this is any reflection of their gender identity as they are no longer alive. This means we are working on assumptions, and those assumptions may well be wrong. Also, consider the age of these photographs; the language that we have today to express our identities did not exist then, and may not have been appropriate to them or something they recognise in relation to themselves.

We should consider the ethical implications of giving an identity to someone who we cannot talk to and ensure that we are not suggesting that such cross-dressing automatically created an LGBTQ+ friendly environment during a time when such expressions were illegal. Until 1861, homosexuality was a hanging offence, and imprisonable, sometimes for life. Understanding of Trans+ identity was even more limited, and not seen as separate to sexuality.

It is not wrong, however, to look at these images and take from them some form of queer interpretation if that is how they speak to you. Queer history can be difficult to find, but an expression that falls outside of cisgender ‘norms’ can be seen as queer without a person necessarily having to identify in such a way. It does not have to reflect them personally but reflect the nature of the act.

Was the Crossing the Line Ceremony a safe space to explore gender identity?

Not necessarily. Even today, anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric, particularly anti-trans+ rhetoric, is a significant problem and growing at a rapid rate. Queer members of the Royal Navy may well have felt incredibly uncomfortably in these spaces, perhaps even questioning why it was acceptable for their cisgendered colleagues to cross-dress when they were unable to do so safely and legally.

However, it is possible that for some it offered a rare opportunity to express who they were for a short while, safe in the knowledge that others around them were dressing in a similar way. Can you see anybody who might have taken comfort from such an opportunity, rather than just seeing it as a chance for some fun?

Crossing the Line ceremony, New Delhi 1950 - image from the NMRN Collection

Today, The Royal Navy is a far safer space than it once was. Attitudes continue to change and evolve; drag races now take place onboard ships, LGBTQ+ networks like Compass exist, and in 2021, a rainbow light show lit up HMS Queen Elizabeth on her global deployment in support of Pride.

We may not be able to take these images as a direct, accurate representation of Trans+ culture within the Royal Navy, but it is evident that the act of dressing up in general, as well as cross-dressing. allowed the space onboard ship for the blurring of gender boundaries.

About the National Museum of the Royal Navy: The National Museum of the Royal Navy have an LGBTQ+ staff network in place, helping to transform the experiences of LGBTQ+ people at work. We provide a space for LGBTQ+ staff and allies to support each other, express concerns they may have, and spend time around people who understand their experiences. The LGBTQ+ staff network feeds into our Equity, Diversity and Inclusion action group ensuring LGBTQ+ staff voices are heard and are considered when developing new policies, processes and initiatives - helping us to become more inclusive.

Glossary

LGBTQ+: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer – the ‘+’ is used to incorporate all other identities such as intersex, asexual, non-binary etc.

Queer: Once just used as a purely offensive term, it has now been reclaimed by many within the LGBTQ+ community and is an accepted academic term. Some people do still consider it offensive, however.

Trans+: Trans is an umbrella term to describe people whose gender is not the same as, or does not sit comfortably with, the sex they were assigned at birth. Originally, it referred to people who transitioned from their sex assigned at birth to the opposite sex, however, today it covers many more experiences and expressions of gender identity, which is where the ‘+’ becomes significant.

Cisgender: Someone whose gender identity corresponds with the sex they were assigned at birth.

Queering history: It is not always possible to find solid evidence of queer history, due to people historically hiding their sexuality or gender identity. Queering history is the practice of finding evidence of self-expression outside of the societal norms of the time. These may not have been an explicit demonstration of sexuality or gender identity but could be interpreted as such.