The story of the Royal Navy’s role in D-Day for D-Day 80

- View news filtered by: Second World War

- View news filtered by: War and Peace

- View news filtered by: Battles

- View news filtered by: D-Day 80

- View news filtered by type: Blog

The D-Day landings, codenamed Operation Neptune, marked the start of the end for Nazi occupation in Europe. Nearly 7000 naval vessels were used during Operation Neptune on the 6 June 1944, ferrying troops to the beaches at Normandy, aiming to liberate France.

The D-Day landings, codenamed Operation Neptune, marked the start of the end for Nazi occupation in Europe. Nearly 7000 naval vessels were used during Operation Neptune on the 6 June 1944, ferrying troops to the beaches at Normandy, aiming to liberate France.

The story of D-Day does not start on the 6 June 1944. Years of intricate planning, biding their time and mistakes made along the way contributed to the largest seaborne invasion in history. While plans to invade France were in consideration following the Dunkirk evacuation in 1940, plans weren’t seriously drawn up until it was considered as part of Operation Sledgehammer and Operation Roundup planned for 1942 and 1943 respectively. British forces initially rejected the operation as they believed it was too premature for such an invasion. Previous failures at amphibious landings also no doubt laid heavy on their minds.

The Dieppe Raid in 1942 was one of these failures, in the end helping greatly to inform plans for D-Day. The assault on the port of Dieppe in France resulted in over half of the invasion force being killed, injured or captured. The Allies learnt that this kind of assault would require considerably more support from the air and from Royal Navy ships offshore. It was also clear that a direct assault on a port in this way would not work.

It wasn’t until Spring 1943 that planning began in earnest for Operation Neptune, and it was realised that a specialist Naval commander was required for the operation - their choice was Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay. Admiral Ramsay was the architect of the Dunkirk evacuation in 1940, earning him a knighthood, so it was clear to see why he was the perfect person for the job. Dunkirk was only the first of Admiral Ramsay’s successful amphibious operations during the Second World War, as he’d done the same in North Africa and Sicily for Operation Torch and Operation Husky.

The role of the Royal Navy during D-Day is often understated; the majority of ships and men during the landings were provided by the Royal Navy. Of the landing craft at Normandy, two-thirds were crewed by Royal Marines. Due to the necessity of invading via the sea, the army would have been unable to set up traditional artillery, so Royal Navy ships took on the role of bombarding the coast in preparation for the landings. 138 warships, including seven battleships, were involved in bombarding the coast of Normandy.

Midget submarines also played a vital part in the lead-up to and on D-Day itself. These tiny submarines could only contain a crew of 4, who lived in cramped conditions with no room to stand, but their size made them perfect for specialist covert operations. X20 conducted reconnaissance of the beaches and took soil samples in preparation as part of Operation Postage Able. On D-Day, two x-craft, X20 and X23, marked the limits of the Sword and Juno beaches, ensuring troops landed in the right location. This task, titled Operation Gambit, was led by George Honour, captain of X23. The crew of these submarines sat off the coast of Normandy awaiting the signal to jump to action. Because of the weather D-Day was delayed 24 hours, making the wait even more unbearable. The signal was due to arrive in the form of a coded message from a BBC broadcast the crew were tuned into. The Royal Navy Submarine Museum has several artefacts related to the work of these X-Craft, including George Honour’s dagger, taken with him on the operation. Additionally, the museum is home to X24 -the sole-surviving X-craft.

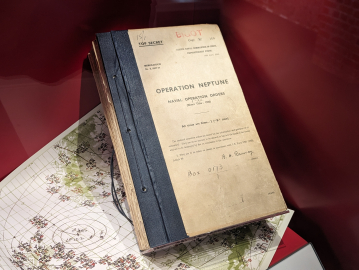

Despite the concerns over the operation, the delays, and the terrible losses on the day, the operation was a huge success. In the first six days of the landings, over 300,000 troops were ashore, alongside over 100,000 tonnes of supplies. The Allied forces had started as they meant to go on, the war in Europe was over within the year. A copy of the plans for D-Day which would have been provided to all the key people is in the collection of the National Museum of the Royal Navy, on display in the HMS Gallery in Portsmouth. This document was intended to have been destroyed following the operation, but was kept, and is signed by Admiral Bertram Ramsay.

2024 marks the 80th anniversary of D-Day, and to commemorate it the D-Day Story has collated 80 objects designed to tell the story of the operation. You can learn more about the ‘D-Day in 80 Objects’ project, on the D-Day Story’s website.

You can read more about the objects submitted by the National Museum of the Royal Navy, in a separate blog post.

If you want a more in-depth look at the Southwick House D-Day map our newly created, interactive map allows you to get a new view of the depth of planning required for 'Operation Neptune'.