Trafalgar Day 2024: Vice-Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson

- View news filtered by: Napoleonic

- View news filtered by: War and Peace

- View news filtered by: Battles

- View news filtered by: Trafalgar Day

- View news filtered by type: Blog

Join the National Museum of the Royal Navy as we launch a new digital series for Trafalgar Day - covering the life of Vice-Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson, the man behind the title, the history of the Battle of Trafalgar, and the enduring legacy of 21 October 1805.

A captain before he was 21. A household name at 39. Killed in action just after his 47th birthday. Horatio Nelson lived a colourful, crowded and short life. He masterminded some of British history’s most resounding victories: the Nile in 1798, Copenhagen in 1801, and Trafalgar in 1805. Losing an arm and the sight in one eye in the process.

He also had a scandalous and very public love affair with Emma Hamilton, despite both of them being married to other people. Affectionate, engaging, and a devoted friend and father. He was also ruthless and occasionally cruel. Despite it all Nelson remains one of Britain’s most charismatic leaders.

Early Life

Horatio Nelson was born on 29 September 1758 in Burnham Thorpe, Norfolk. At 12 years old, he joined the Royal Navy under the patronage of his uncle, Captain Maurice Suckling. Overall, he was a bright, engaging child. Naturally impulsive and constantly seeking attention and approval from adults, these strands would run right throughout his life and provide the underlying pattern to all his actions, public and private.

His Naval training was unconventional. After a short spell on HMS Raisonnable, he made a voyage to the west Indies. Then, aged only 14, he took part in an expedition to the Arctic and completed his training with a two-year stint in the frigate HMS Seahorse in the East Indies. Captain Suckling seems to have intentionally planned for the young Horatio to enjoy as wide a variety of experiences as possible. Suckling also gifted the young Nelson a text book on navigation titled ‘The Longitude Found’, which is on permanent display at the National Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth.

In 1775, he fell dangerously ill with malaria, to the extent he had to be invalided at home. After a couple of years, Nelson was recovered enough to pass his lieutenant’s examination on 5 April 1777. Less than a year later he was promoted to commander and was given his first independent command, the brig HMS Badger. Six months later he received the key promotion to post of captain, when he was still three months short of his 21st birthday. Following his promotion, Nelson spent eight years almost continuously in command of frigates.

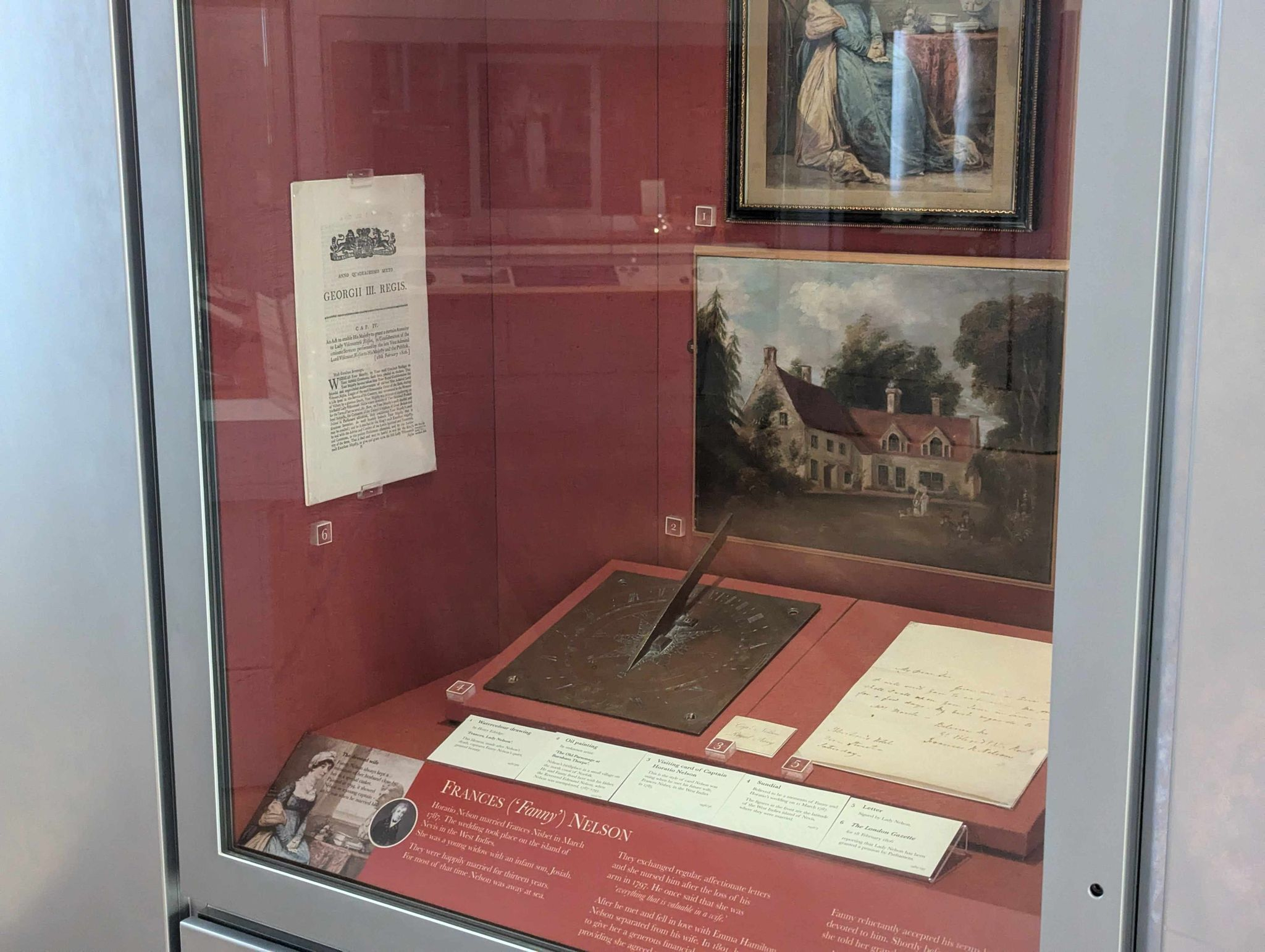

On 11 March 1787, Nelson married Frances (Fanny) Nisbet, who he met on the island of Nevis. Their courtship was warm and affectionate, but the marriage was severely tested in its early years when they returned to Burnham Thorpe. Unable to obtain another appointment in the Navy, Nelson became frustrated and irritable, while Fanny, used to the warm climate and relative luxury of the West Indies, had to adjust to genteel poverty and the icy winters of Norfolk.

A Rising Star

Nelson’s six years of inactivity ended in February 1793, when war broke out with revolutionary France. He was offered command of the 64-gun battleship HMS Agamemnon. Having gathered a ship’s company, including a large, hand-picked contingent of men from Norfolk, he sailed to join the Mediterranean fleet, under Admiral Lord Hood. So began an important stage in his career, one which gave him experience of independent command when he took important operational decisions by himself.

In 1794 Hood gave him command of naval forces ashore during the capture of Corsica, and he was present at the siege and capture of the two key towns Bastia and Calvi. At Calvi he lost almost all sight in his right eye when he was hit in the face by gravel thrown up by a French cannonball.

In 1795 he had a brief spell with the main fleet, by then commanded by Admiral William Hotham, and for the first time took part in two fleet battles. At the Battle of the Gulf of Genoa (1795) he showed his independent spirit by taking the Agamemnon to attack a disabled French ship, the ÇaIra.

He was then detached to the Mediterranean coast of Italy as a commodore in command of a small squadron, in its fight against the French armies under the rising new general Napoleon Bonaparte.

In these years his exploits won Nelson the regard of a number of influential people – notably the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Spencer, and the new commander-in-chief in the Mediterranean, Sir John Jervis.

When the combined French and Spanish fleets took refuge in Cádiz, the Admiralty began assembling a fleet to deal with them. The command was offered to Nelson. Nelson joined the fleet onboard HMS Victory, off Cádiz on 28 September. The next day, he held a dinner party on HMS Victory, at which he explained his plan for defeating the enemy – ‘The Nelson Touch’, as he called it. The man who had seized the initiative at Cape St Vincent eight years before was now empowering his subordinates to do the same.

The Decisive Battle

The Battle of Trafalgar unfolded very much as Nelson had planned. One British division, under Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood, enveloped the allied rear, crushing it with superior gunfire, while another under Nelson smashed through the centre of the allied line. Having led the way through a hail of shot, the Victory became entangled with a smaller French battleship, the Redoutable. It was from the Redoutable’s rigging that the bullet which struck Nelson was fired, at about 1.15 pm. Nelson was pacing the quarterdeck with Captain Thomas Hardy as he was hit.

His last words were, ‘Thank God I have done my duty.’ Of the 33 French and Spanish ships that had begun the battle, 18 had been either captured or destroyed, four escaped only to be captured a fortnight later and 11 managed to struggle back into Cádiz.

After Trafalgar

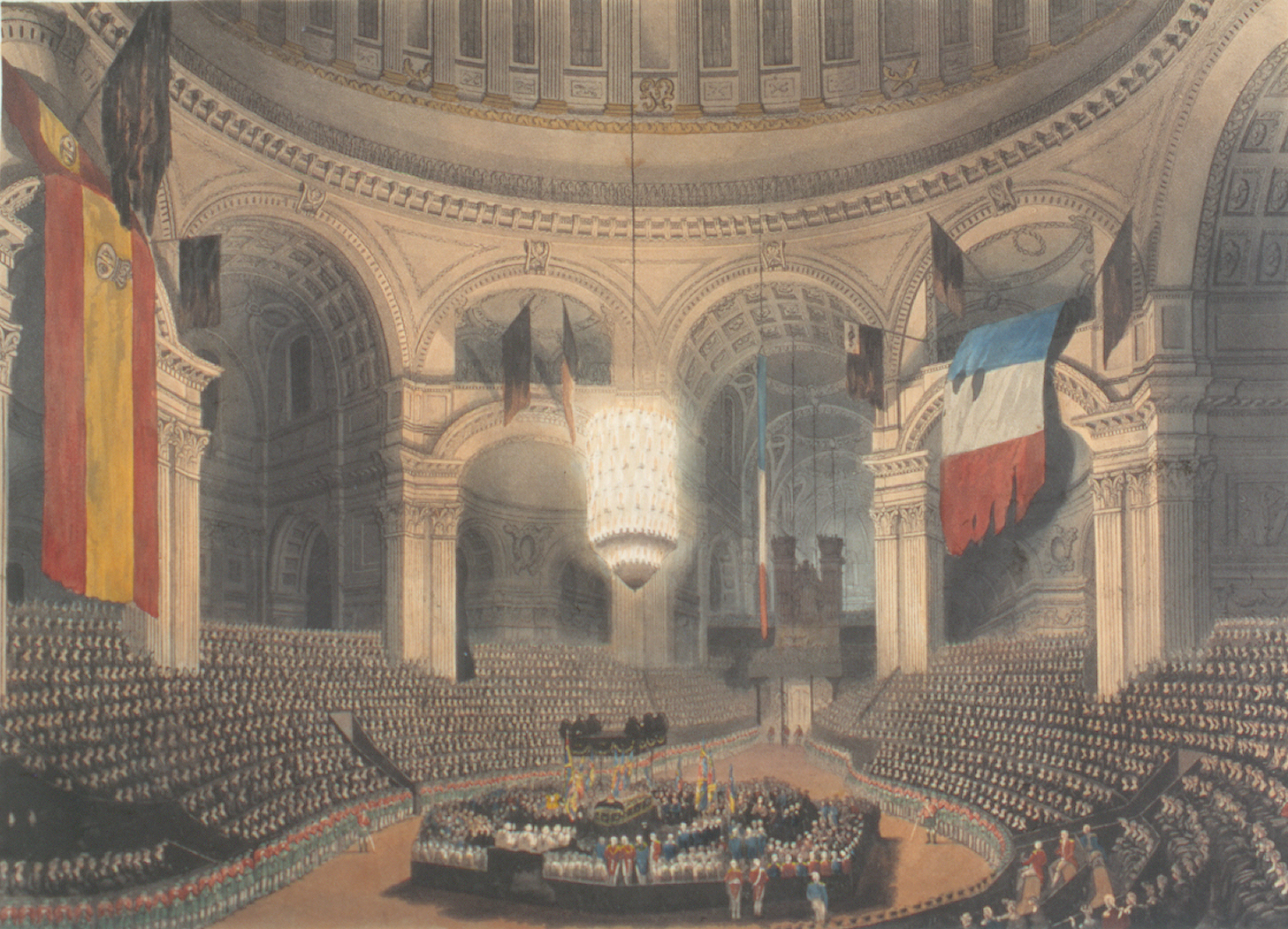

Today the spot where Nelson first fell is marked onboard HMS Victory, as is where he died on the Orlop deck. The death of Nelson had a huge impact on the British public, his death in the hour of victory no doubt made it all the more tragic. Nelson was the first non-royal to have a state funeral at St Paul’s Cathedral, his coffin was carried by barge up the Thames, and St. Paul’s itself was flanked by huge captured French and Spanish flags from Trafalgar. Some artefacts from the funeral still survive, including the funeral barge that carried Nelson’s body to St Paul’s which is on display in the Victory Gallery.

So great was the feeling towards his death, there was even prize money offered to create the greatest depiction of his final moments during the Battle of Trafalgar. The eventual winner was Arthur William Devis with 'The Death of Nelson, 21 October 1805', a copy by the artist is currently on display in the Nelson Gallery. Here Nelson is seen in his dying moments flanked by Captain Hardy and other key figures onboard, including the ship’s surgeon and his chaplain. Devis actually went onboard Victory and met some of Nelson’s crew to sketch them for the piece, and to get an idea of where he died. The final painting is Christ-like, with a shirtless dying Nelson looking up while being bathed in light. This in itself says a lot about how people saw him.

You would be forgiven for thinking Nelson’s story does not seem to have much relevance to today’s Navy. Wooden sailing ships with cannons firing is a world away from the 21st-Century battlefleet with its aircraft and submarines, computers and satellites. But behind the technology there are many constants. Technology is only as good as the humans who operate it, particularly in the unforgiving environment of the sea. Nelson understood the importance of caring for his crew and the need to communicate clearly with his officers, often doing so face-to-face at dinner in his flagship. He gave them confidence to use their initiative within the strategic plan. And he embodied the Navy’s role as a fighting force, whose role was to seek out, engage and destroy the enemy, to make the world a safer place.

Nelson gave ‘form’ to all that the Navy had stood for in the centuries up to 1805 – service and success.

His legend has equal meaning two centuries on.

To learn all about Nelson, his illustrious career, and the public’s reaction to his death in the final moments of one of Britain’s greatest naval victory, visit the Nelson Gallery at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard. This gallery features everything from medals won by sailors during his most influential battles to Nelson’s personal affects and letters.